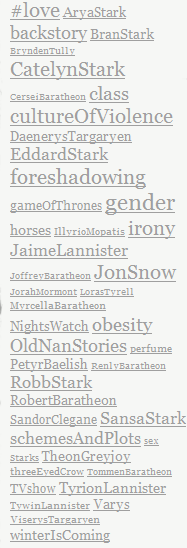

Characters I ended up paying special attention to this reread, some on purpose, some not:

Catelyn Stark:I tried really hard to give Catelyn the benefit of the doubt on this reread, yet ended up actually liking her less than I did before. She’s a good person and generally thinks she’s doing the right things, but her stubbornness and self-absorption keep preventing her from seeing the true effects of her actions.

Robb Stark:Prior to this reread,I remembered Robb as an uninteresting stock noble-young-prince from central casting, and was fascinated by the way many readers seemed to project depth and nobility into his character. Paying special attention to him on this reread, I found his character a bit more fully developed on paper than I had thought. Not much more so, though, and not in particularly interesting ways: he loves his brother, loves his mom but wishes she wouldn’t treat him like a kid, feels overwhelmed when thrust early into a position of leadership. Pretty (deliberately) clicheed stuff there. And if he’s supposed to be a military genius, it’s not coming across to me: his strategies don’t seem that radical, and surely his advisors — particularly Brynden — have a lot to do with them?

Ned Stark: Here I have to take issue with the common “being too honorable was his downfall” characterization. Ned actually shows a reasonable degree of political awareness and is under no illusions about the honor of the Lannisters or the Small Councillors. Sure, Littlefinger played him, but Littlefinger has successfully played just about every character in the novels; besides, Ned didn’t so much foolishly expect him to behave honorably, as falsely believe he’d gotten to the bottom of his dishonorableness. And warning Cersei was a big mistake, but it was an error born of compassion, not “honor” (as the example of Stannis shows, compassion is if anything antithetical to Westerosi ideas of honor and justice).

If Ned has a central tragic flaw, it’s his blindness to the true nature of his “best friend,” Robert. Ned’s insistence on behaving as if “the Robert he had known” had his back — even after the Robert he knew *now* had repeatedly demonstrated that he didn’t — made him think he was far safer than he was. (Not to mention that, just as Ned was never the boy he once was, Robert quite possibly never was the noble “Robert” Ned thought he had known. But that’s something we’ll see more clearly in later books.)